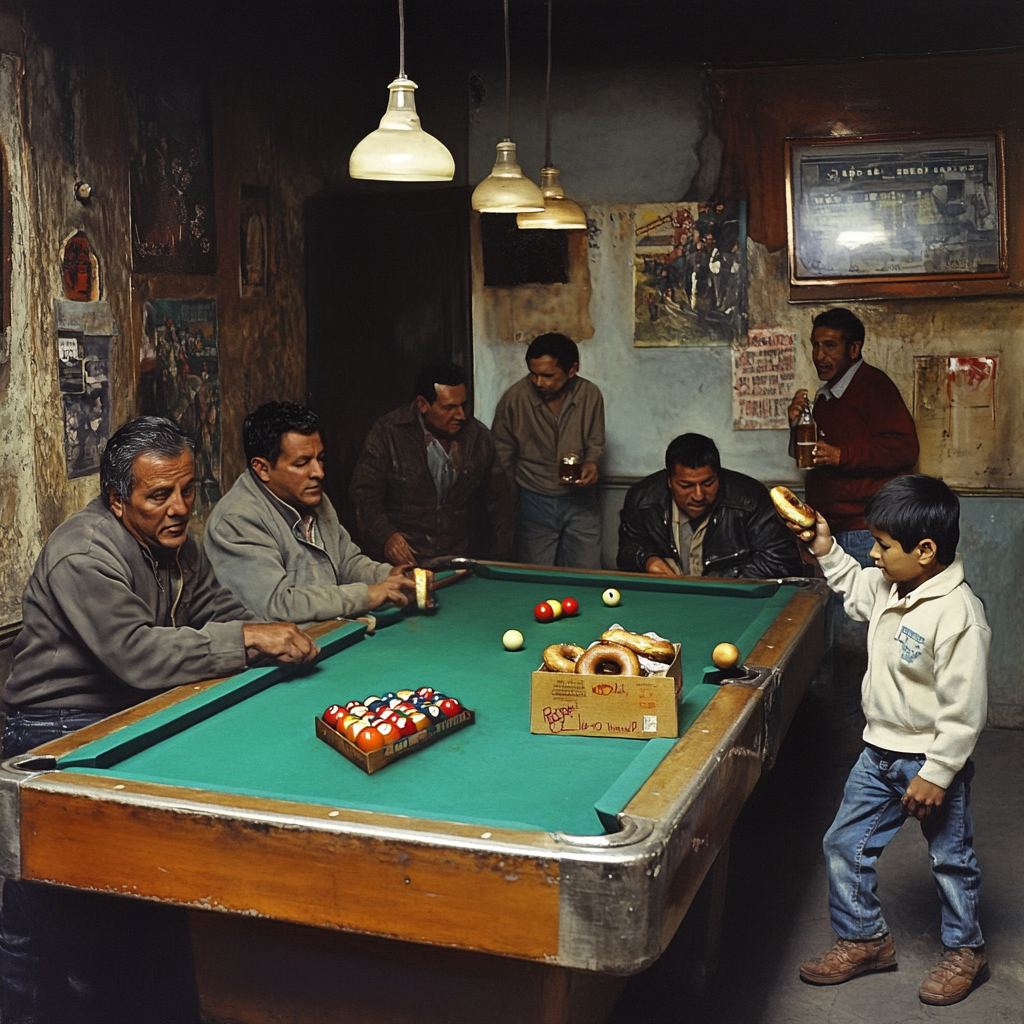

Dad loved going to the Tampico on weekends to play pool, drink beer and hang with his friends. The Tampico was the only real Mexican bar in the neighborhood and was located on 4th and Macdonald in Richmond, a working-class city dominated by Standard Oil, the biggest refinery in Northern California. The Tampico was only a few blocks from our home on the “good” side of the tracks that separated the poor part of the town with the growing population of Mexicans from North Richmond, the unincorporated side of town where most of the blacks lived. My mother would often send me to the Tampico to see if he was winning at pool and to bring back as much of his winnings as I could convince him to give me to take home. It all depended on how loaded he was and whether he was on a winning streak, which was often the case.

Dad’s drinking buddies were all working class men who had little or no education. He reigned over them as he was a master welder, a champion pool player, and darn good at the races where he studied the horses and jockeys. During the racing season he would go to Golden Gate Meadows with his fellow race buddies where they would spend the day comparing race notes, placing bets, and drinking beer. He won far more often than his friends as he took the time to study the racing stats and he used an old set of binoculars to study the horses and their jockeys.

Richmond was then and still is an East Bay city, known by many in the San Francisco area as the armpit of the Bay Area. The city was controlled by a handful of white businesspeople and old school WW2 veterans who squeezed what they could out of the city that supplied the workers to man the round the clock shifts at Chevron and American Standard. Dad was a master welder and worked at American Standard, the only other major local employer that produced toilets, sinks, and like goods. The Tampico was the prime water hole for my father and the other Mexicanos who worked at Chevron, American Standard, and the few remaining shipyards that lined the Richmond harbor.

Most of his buddies and close family members called him Don or Jefe Cuco, as Cuco was his nickname and they looked up to him as a leader, a jefe. He was always pissed off at the city council and police who he called corrupt and self-seeking ‘pendejos’, idiots. When I was in fifth grade he banded together with his friends and launched La Gente (The People), the first Mexican based community organization in Richmond that focused on community concerns. The time was ripe as his small organization grew quickly and drew the attention of the Anglo power brokers. His goal was to educate and organize the Mexican community to support our community to provide needed services. La Gente soon became a beacon for the Mexican based community and created alliances with other organizations, ranging from a partnership with the Catholic Churches in our community to bury the deceased Mexican poor with dignity. Dad and his supporters also sponsored several sports clubs and events, including a boxing club that sponsored fights that generated income for La Gente. While Dad avidly supported my book reading habit he also wanted me to learn how to fight so he insisted I join the organization’s youth boxing club. Growing up in Richmond required several skills, including knowing how to fight, both the clean and street ways. In short Dad was a born leader but he was also an old school Mexican who played as hard as he worked and the Tampico was his primary playground where he held court, gambled, played pool, and drank.

Dad grew up in Zacatecas and never knew his father who died in a mining accident, somewhere in northern Ariona. He was a gifted boy who worked to support his mother as soon as he could walk a donkey to the mountains to collect firewood to sell to the local women for cooking. There were no schools in his small mountain town, so he grew up without the benefit of a formal education. While he never attended a day of school in Mexico and taught himself to read and write in Spanish and English and education for his children was a given. He pounded the value of education into our heads and was very proud when we brought home our report cards with good grades. Unlike most of my cousins’ parents, Dad and Mom always attended the parent teacher meetings and they took special pride when we were recognized at school for whatever reason. So, he was OK with my going to the Tampico to ask for some of his winnings to take home as it gave him a chance to brag about his number one son, me.

One of Dad’s cardinal rules was that I could keep half of whatever money I earned from doing yardwork for neighbors and selling things that I picked up in Mexico. I never had an allowance and learned early how to sell whatever might bring in a few coins, from the eggs laid by our chickens in our backyard to fireworks I brought back from our regular trips to Mexicali to visit his brother and my Mexican family in Cucapah, an ejido, just south of the border. I loved those trips where I ran across the corn fields and took skinny dips in the irrigation ditches with my Mexican cousins. I always took my savings with me and did a booming business after every trip to Mexico with Dad as I always brought back bags of fireworks, including M2s, firecrackers, sparklers, and rockets. The fireworks were hot sellers in school until a couple of my friends and cousins blew up a few of the toilets at our elementary school. One of my school customers guys snitched on me and I got off with a few swatches from the school custodian. I was forced to abandon that business and looked for other revenue sources.

By age ten I had diversified my sources of income beyond mowing lawns, doing yardwork, and running errands for Mrs. Negus, a wheelchair bound Anglo neighbor and a surrogate mom to me. I loved Mrs. Negus whose son had died in WW2 leading a bombing raid over Germany. She had a big yard that always needed attention. We would often share ice cream and a donut after I finished the yard work and one day it dawned on me that the Tampico might be a good place to sell donuts as I could buy day-old donuts for twenty-five cents a dozen and maybe sell them for five cents each. A dozen could net me almost fifty cents and two dozen might bring me a dollar, big money back in the early fifties.

I bought two dozen donuts one Sunday morning after going to mass with Mom and my younger sister and brother. Mrs. Negus had paid me fifty cents the day before for doing the lawn and bringing her a few things from the local store. That fifty cents bought me two dozen day-old donuts, one dozen of the glazed and the other a mix of old fashion and chocolate topped. It was around noon when I arrived at the Tampico and it was louder than usual as it was filled with boisterous men playing pool, drinking beer and hard liquor, and arguing about the Giants game that was on the radio. Dad motioned me over and asked what I was carrying, and I showed him my donuts. He took a glazed one, ate it quickly and asked if I was taking the rest of the donuts home. I told him no and that maybe his friends might like a donut or two and that I would take the leftover donuts home. He motioned to his buddies to come over and they started reaching for the donuts. I gathered my courage and said that the donuts were five cents each and within a few minutes I was sold out. For the first time Dad told me I could keep all the profits and to not tell my mother about my new business at the Tampico as she would brag to her friends and I could end up with competition from their own boys. I wasn’t too concerned about that as I knew my father was the Tampico king and would protect my new business venture.

After that first donut day at the Tampico, I was a regular on Sundays and within a few weeks saved enough money to buy a decent fishing pole, a good used bike, and lots of second-hand books. The Tampico was good to me as long as the day-old donut supply lasted. I still like donuts, especially the old fashion glazed ones, as it reminds me of the good old days of donuts at the Tampico.