I finished high school in the summer of 65. It was a proud time as I was the first of the extended family to earn a High School Degree. That summer I was also admitted to UC Berkeley and would start in the fall quarter. I could see and smell the changes on campus and the Bay Area. Life was buzzing early that summer. People in my community were protesting the war, demanding race and ethnic equity, and demanding social change. It was going on everywhere. I joined in as best I could. A few friends and I helped organize Vietnam war protests. We also helped organize grape boycotts at Safeways markets in Oakland and the East Bay. It was a crazy time of good and bad stuff happening and I wanted to be part of the change, whatever it was and wherever it was happening. Our government’s ramping up the Vietnam conflict detonated even more protests by students and others around the world. People, especially students and the young, were making their voices heard the Haight to Saigon, London, DC, Paris, Mexico City, Istanbul, and beyond. I wanted to be part of the change and I had a dime to drop so it was the right time to leave the hood and family expectations behind, and hit the road for the summer.

My hormones and desires were raging and I wanted a break away from the family, the hood, and even my close friends. I had read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road earlier that year and I thought it would be cool to hit the long road to the ancestral lands Chicano style. My first year at Berkeley was ahead of me and I wanted a summer to remember.

Motivation also came from the fact that my father and I had not been on good terms for most of the last two years. We were tired of ignoring each other when not debating which was most of the time. I knew a little of his roots. Per his telling his own father, my unknown grandfather, died in a mining accident in Arizona a few months before he was born. The story is that he died with a book in his hands as he could read and write. Dad was raised by his mother and older siblings in Juchipilla, a small mountain town. He told me a few times when he was lucid drunk that there were many hard times when food for the family was not certain and many people were so desperate to eat they did unthinkable things. He was the baby of the family and they fed him what they had. As a young man of eighteen Dad made it on his own through the mountains of Zacatecas to the border and found refuge and learned new skills at the Kaiser shipyards in Oakland. In a short time he was a master welder and made a family in Richmond. It was time to check out my father’s homeland and see what he was made of. Bur before going I had to meet with the head of the family, my Abuela Victoria.

My abuela lived about a half mile from my home and I frequently saw her. She was the rock back then and still stands strong today. Mom was glad that I visited say goodbye my Abuela. We both knew Abuela would not let me leave without offering some advice. Mom was right as Abuela sat me down for a quick talk. First, she pretended to scold me for doing such a menso (stupid) thing by going alone. Then she told me again how she had escaped revolutionary Mexico when Pancho Villa was raiding along the border. He wanted her to join up with his band but she said no and headed north. She ended up in Richmond after working the vineyards of Sonoma and Napa. I told her about the trip and she lit up one of her special hand rolled cigarros.

Abuela gave me her smoke blessing and said she was filled with pride that I would make the journey. She told me that I needed to take some things with me just in case so that I could handle different situations. Her first contribution was a three inch long pruning knife that had been in the family for decades. It was razor sharp and slept in a handsewn leather case. She also gave me a bunch of cigarette lighters, an old deck of loteria cards, several rolls of quarters, and a small ball of rope. She also gave me a small cloth sack and told me that I should open it only when I needed to get out of a real bad problem. She opened the sack and showed me a $10 Liberty Head Eagle Gold Coin. I knew that coin was not legal tender in the US but was much wanted for elsewhere. She told me that I could use it only for an emergency and not for drink or putas. Finally, she handed me another small bag with a dozen or so of her hand-rolled curada joints. She said the Mexicans wouldn’t check me at the border and to take everything over the border I could get away with.

The backpack was ugly and I hoped did not look promising. It had a big mouth closed with a thick cord and one zippered side pocket. I had crammed it full of stuff, including some skinny jeans, khaki shorts, swim trunks, thick socks, a few days’ worth of chones, a plastic rain coat, and a couple Giants baseball hats to use for trade. My mother forced me to take some emergency food for desperate times like nuts and my own home-made beef jerky. My Abuela’s items were tucked into the backpack’s side pocket for quick access.

So, I said goodbye to my family, put on my boina, strapped on my very full backpack and walked to Carlson Blvd. where I stuck out my thumb. Carlson was our town’s artery to the rest of the East Bay and beyond and I was ready to ride it to the end and beyond.

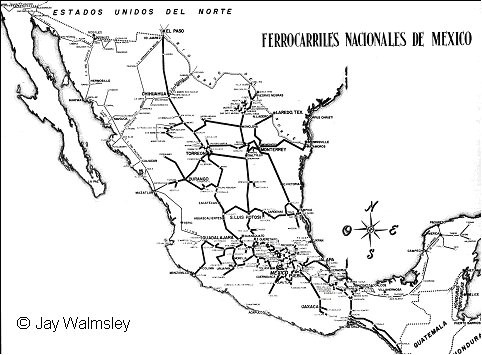

Hitchhiking was common back then and over the previous year I had practiced my hitchhiking skills around the greater San Francisco Bay Area, including jaunts to Muir Woods, Bolinas Bay, and up the coast. I was used to hitchhiking alone and was often picked up by other students, including UC Berkeley students who lived nearby. I wasn’t sure how long I would be gone but knew I knew I had to travel fast and cheap. So, my plan was to hitchhike as far as Mexicali and then take cheap buses and trains the rest of the way, whatever the way might be.

Luck was with me as I was picked up in less than fifteen minutes by a couple of Berkeley students who had just finished the quarter and were driving south to their home in Visalia. Both of the white guys were a few years older than me and they thought it was cool that I was making a solo trip to Mexico. Over the six hours it took to get to Visalia they smoked a lot of dope and stopped three times to buy beer. They took turns driving and drinking beer and were getting pretty sloppy so I asked them if I could drive. They were happy to let me drive as they were stoned on weed and beer. I drove the last few hours until we arrived in Visalia in the late afternoon. They left me off on Route 99 just south of Visalia and offered me some smoke thanks for driving but I declined as I had a long way to go and didn’t want to get lost in a fog first day out.

I stuck out my thumb and got picked up by an old guy who said he was going to Barstow to pick up some farm equipment. Said he wanted some company to stay awake. It was a weird ride as he spent the entire time telling me about his last time in jail working in the kitchen when a riot broke out. According to him one of the senior guards was taken hostage by the prisoners. He was in the kitchen and claimed he rescued the guard from the prisoners by threatening them with the knife. They let him out early for rescuing the guard but he was still on parole and couldn’t be caught drunk. He told me all this while taking swigs of cough syrup. He had one bottle left in the bag on the floor next to my feet and he would motion to me for the bottle. He stopped at a truck stop and said he would be back after buying more cough syrup. While waiting I picked up a beat-up issue of Life magazine that featured the prison riot on the cover and a story about him and the rescue. He was legit but I didn’t want to wait for him so I got out of the pickup and stuck out my thumb for a fresh ride. It was getting dark and the backpack was peeling the skin on my back I was worried that I might have to find a place to crash for the night if I couldn’t catch another ride.

Fortuna was with me as I got picked up in just a few minutes by a Chicano sailor in a classic 56 Chevy, a red and white beauty. He had just filled his tank when he saw me and asked where I was going. I told him I was going to Mexico by way of Mexicali but he said that he was driving to El Paso where he had some friends. His name was Rudy and said that he really needed to get to El Paso fast as he had just gone AWOL from the navy as his ship got order to go to Vietnam. Rudy was confident his El Paso friends would take him in and that he would party until the Navy found him. I could tell he was wired on whites and I decided that El Paso could work. We took turns driving through the night. We arrived in El Paso mid-morning. It was brutally hot and the wind was screaming and throwing sand at us. Rudy stopped at a bar near city center and said his friends would meet him there. I wished him good luck with his unauthorized leave and he gave me an abrazo and passed me a small bottle of whites. It was getting late and I wanted to be out of El Paso by train as soon as possible as the town did not look inviting to me.

It took me a couple of hours to make my way through El Paso to the border crossing. I arrived and spent a few minutes on the Juarez side taking in the city. It was boiling with human and auto activity. It was getting dark as I walked to the border and the Mexican customs guard just waved me through. The smell was pungent with the exhausts of the jammed busses, beat up taxis, overloaded trucks and scarred cars fighting for space on the streets. Juarez was truly alive, unlike any other city I had seen. She was a fallen angel of a city as was dirty, loud, and full of Mexicans from both sides of the border who came to her for relief.

Since my goal was to get to the train station as fast as possible I decided it was worth the buck to take a battered taxi to take me to the central train station. It was a ride out of cartoon movie as we fought our way to the rail station that was a beehive of human activity. I bought a second-class ticket to Chihuahua that cost five dollars. The ticket fit my budget of spending no more than twelve dollars a day for everything, including food, lodging, and transportation. My second-class ticket did not guarantee me a seat but I pushed my way to a spot on a wooden bench. I hadn’t slept for more than an hour or two at a time over the last two days and I was ready to pass out. Somehow, I stuffed my backpack under the bench and tied it to my leg with a piece of rope from Abuela’s stash. I fought to stay awake as other people with sacks and bags crowded around me as the train belched and lurched its way past Juarez and into the desert night.

I had grown up next to the tracks and loved seeing all the sleek Santa Fe locomotives that swept past our backyard several times daily. The Santa Fe station was less than two miles from our home and was the end of the rail line that started east of Chicago. I often walked there to see the most beautiful trains in America. The Juarez locomotive pulling us across the desert was not a beauty like those I grew up with. This Mexican train was an ancient iron and steam locomotive that looked like it had seen action in old western movies. The passenger cars were sooty with broken windows, worn wooden benches, and light fixtures that blinked off and on. All of the second-class wagons were full of men wearing soiled white shirts and pants and a few women hiding under their huipils. Most of my fellow passengers were carrying sacks of goods and a few of them had live chickens on sticks and goats lashed to their legs. My compartment reeked of burnt coal as black smoke surrounded us while we rolled from side to side. For the first few hours the train stopped every few minutes at small stations as people and animals boarded and others got off. It was clear that this train was the arterial track for people and their goods and livestock. The train’s rhythm spoke a new language to me and I listened carefully as it was impossible to sleep with the smoke and noise. I was also concerned about two guys about my age who stared at me and checked out my backpack under my feet. I was clearly a pocho from the north with a weird Spanish accent in my gringo jeans. I didn’t rest my eyes for a moment until they got off at one of the rural stations.

It was long past midnight when the train slouched into the Chihuahua train station. Despite being late there were pools of people moving along the train platforms while pubescent indio looking soldiers patrolled the area with their vintage rifles and shabby uniforms. I was exhausted, dirty and ready for some food and a bed. Heck of a way to kick off my Mexican rail adventure.

Mexican Rail System in the 1960s